- Three Alpha

- Posts

- When a galaxy is pulled apart

When a galaxy is pulled apart

Studying what's left can tell us about dark matter.

Welcome to Three Alpha! Since last time: In the Solar System, Theia, the planet that almost destroyed the Earth and created the Moon, came from the inner solar system; in the Galaxy, we’ve made the first ever detection of a coronal mass ejection from another star; and in the Universe, astronomers seem to have finally found examples of the first stars (known as Population III stars) in an early galaxy.

Meanwhile, in this edition of the newsletter we’re focusing on what happens when small galaxies encounter large ones. Read on for more…

A trail of stars

The gravitational pull, once imperceptible, strengthens as the spiral galaxy looms ahead. The dwarf galaxy was once millions of light years away from its larger cousin. That may feel like a safe distance, but it is not too far for gravity. The spiral galaxy’s gravity reaches across the intergalactic void and grabs all that it finds. Over the course of billions of years, those millions of light years have dwindled to a few tens of thousands. The dwarf galaxy is still holding it together, just about, as its own self-gravity overcomes that of the spiral. That won’t last much longer.

Three Alpha is a free newsletter sent every other Saturday. Not subscribed yet? Make sure you don’t miss future editions by subscribing now!

Soon, the dwarf will get close enough to the spiral for the larger galaxy’s gravity to overwhelm the dwarf’s cohesion. Its stars’ paths will become dominated by their orbital motion around the spiral rather than their orbits around the dwarf’s centre of mass. Gradually, the dwarf’s stars will get smeared out along its orbit. It will cease to exist as a galaxy, its stars no longer bound to each other, but instead orbiting the spiral. They will still be together, as a stellar stream, streaking across the darkness, but they will no longer be their own galaxy.

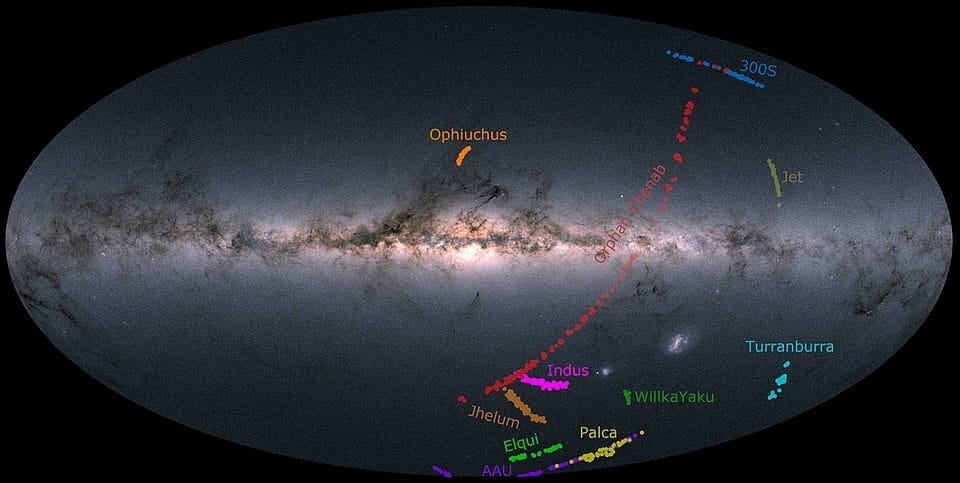

A map of the Milky Way’s stellar streams. Credit: Ting Li (Southern Stellar Stream Spectroscopic Survey-S⁵ collaboration) (CC-BY-SA 4.0)

Occasionally, as the stream loops around its new host, the stars will encounter a clump of invisible dark matter. The matter may be unseeable, but its gravity is just as real as that of the stars, gas, and dust that make up the visible part of the galaxy. Each time the stream encounters a clump of dark matter, it is perturbed, distorted from its straight shape. Those distortions will serve as a record of what the stream has passed through. One day, astronomers down in the galaxy will look up at the stream and see the imperfections, using them to piece together a map of the dark matter.

Stellar streams like this are the remnants of the galaxy mergers that help large galaxies grow. Streams are strewn all around large galaxies like the Milky Way, and studying them and the ways they’ve been distorted is an important way that we can measure and map the dark matter in the halos of galaxies (i.e. in the area surrounding the visible part of the galaxy).

A composite showing M61 in colour (from the PHANGS survey) and the new stellar stream in black and white (inverted, so stars are dark). Credit: Romanowsky et al. 2025, RNAAS.

The Vera Rubin Observatory has recently discovered a previously unseen stellar stream trailing from the spiral galaxy M61, even though Rubin still has not yet started its main observations (that should hopefully begin in the next few weeks). This new discovery comes from the “First Look” images released in June showing the Virgo Cluster. Those images are just a small sample of what the observatory will obtain. In other words, this new stellar stream is yet another sign of just how much amazing stuff Rubin is going to find once the survey properly starts in 2026.

Finally

The Gemini South observatory has turned 25! To celebrate they’ve released a new image of the Butterfly Nebula:

What is Three Alpha? Other than being the name of the newsletter you’re reading now, the name “three alpha” comes from the triple-alpha process, a nuclear chain reaction in stars which turns helium into carbon. Read more here.

Who writes this? My name is Dr. Adam McMaster. I’m an astronomer in the UK, where I mainly work on finding black holes. You can find me on BlueSky, @adammc.space.

Let me know what you think! You can send comments and feedback by hitting reply or by emailing [email protected].